Amazon’s Meteoric Rise

September 12, 2020

Today, Amazon is one of the most powerful companies in the world. It has revolutionised online shopping, by making every conceivable consumable available through its online marketplace and mastering a seamless and consistently reliable shopping experience for its customers. Amazon’s latest financial reports states that it made $75.5 billion dollars in sales revenue in the first quarter of 2020. Every day, Amazon ships approximately 1.6 million packages world wide. Like its namesake, the Amazon River, it became the retail store that dwarfed other retail stores.

In this article, I explore the key components of Amazon’s business model that led to them becoming a trillion dollar company, as well as some of the criticism that has been levelled against it.

Humble beginnings

Amazon was started in Jeff Bezos’ garage in 1994, in Washington, Seattle. Back in the 1990s, retailers only had to pay sales taxes for purchases made in the state it operated in. Bezos thought that having Amazon operate out of a heavily-populated state like California or New York would significantly increase its tax liability, so he settled for sleepy Seattle.

The name “Amazon” was chosen for a number of reasons:

it started with an A, so it would always be first in any alphabetized list,

it sounded different and ‘exotic’ to Jeff,

and the fact that Amazon River was so big, it dwarfed other rivers.

Bezos planned to build something that would one day become the biggest online retailer in the world, dwarfing and ultimately swallowing other retailers. It was going to be “The Everything Store” — a market place not confined by a physical structure or even physical limitations on how much it can stock or process. To achieve this goal, Bezos realized that Amazon would have to start small, and so it started by selling books online.

Jeff Bezos in his tiny office in 1999, with a spray-painted Amazon.com logo

The website was launched on 16 July, 1995 and only sold a selection of books. Within one month of its launch, Amazon had already sold books to people in all 50 states and in 45 different countries. Bezos thought that the most promising products to sell online included were, among other, CD’s, computer hardware, computer software, videos, and books. The concept of online shopping with a reliable window of delivery appealed to many people that lived in rural areas or were frustrated with stores that did not stock rare or unpopular items, like chunky textbooks.

It was a crazy time for the young startup. New employees were interviewed by Bezos himself, and were expected to work 60 hour weeks. Amazon’s customer base was growing so fast that the gap between the number of orders placed and the number of orders shipped was widening. This issue came to light right before the 1998 holiday season. This led to Operation Save Santa, which was a call for all hands on deck — employees from all divisions pitched in to help with the packaging of parcels, doing night shifts and bringing their family and friends to help out. That chaotic holiday season paved the way for the enormous and highly optimized supply chain system that Amazon is famous (or infamous) for today.

The importance of cashflow

While Silicon Valley was partying, Amazon was saving every penny and investing in stimulating future cash flow. The fundamental flaw in many failed DotCom startups was that they lacked well-thought out business plans or paths to profitability. It was a race to the IPO, or being acquired (the so-called “exit strategy” of many smooth-talking entrepreneurs), and so many DotCom startups spent up to 90% of their budget just on marketing. Meanwhile, Bezos invested heavily in the company’s infrastructure to support sustainable growth. In the annual letter of 2001, Jeff Bezos highlighted:

“When forced to choose between optimizing the appearance of our GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we’ll take the cash flows.”

History is defined by a series of critical points, and Amazon’s path was no different. Amid growing concerns that nervous suppliers might ask to be paid more quickly for the products they sold, Amazon realized that it needed to have a pile of cash on hand. Even though its sales were growing by 30%–40% every month, it was still posting massive losses every quarter. With Y2K no longer a concern, the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates and thus increasing the cost of borrowing. This had the adverse effect of discouraging investment.

To ensure that it had a strong cash position to pay suppliers, Amazon sold $672 million in convertible bonds to investors in Europe a mere month before the DotCom bust on March 10, 2001. This was the critical decision that ensured Amazon’s survival through the DotCom Bust, when investor funding dried up and internet adoption temporarily slowed down. During this time, Amazon stock price fell from $107 to just $7. Today, Amazon’s share price is north of $3000. The tremendous success of Amazon today is a testament to long-term thinking and a focus on providing excellent service.

Amazon has, as of yet, not posted a single dividend since its IPO in 1997. Instead, it has invested every bit of cash generated into infrastructure, improving the customer experience, and new revenue streams such as Amazon Prime, Amazon Web Services and, most recently, the Alexa voice computing platform. Amazon has shown that focusing on cash flow, rather than profits, is a sound strategy for creating longterm shareholder value.

Notorious frugality

Working at Amazon in the early 2000s was nothing like working at other tech startups of that time. Your work computer would be functional but not top-of-the-line. There were no free massages or free meals, like at Google. Only coffee and bananas. You paid for your own parking. The salary and stock options were modest compared to other tech giants. No business-class flying or billing expensive corporate dinners to the company. And whenever Amazon moved to new offices, Bezos had them furnished with cheap desks made from wooden doors.

Amazon’s frugality stemmed from Jeff Bezos own frugality. Even though he was worth $12 billion in 1997, one of the wealthiest people in the world at the time, he still drove a modest Honda Accord. He explained this philosophy to a reporter that questioned his frugality:

“It’s a symbol of spending money on things that matter to customers and not spending money on things that don’t.”

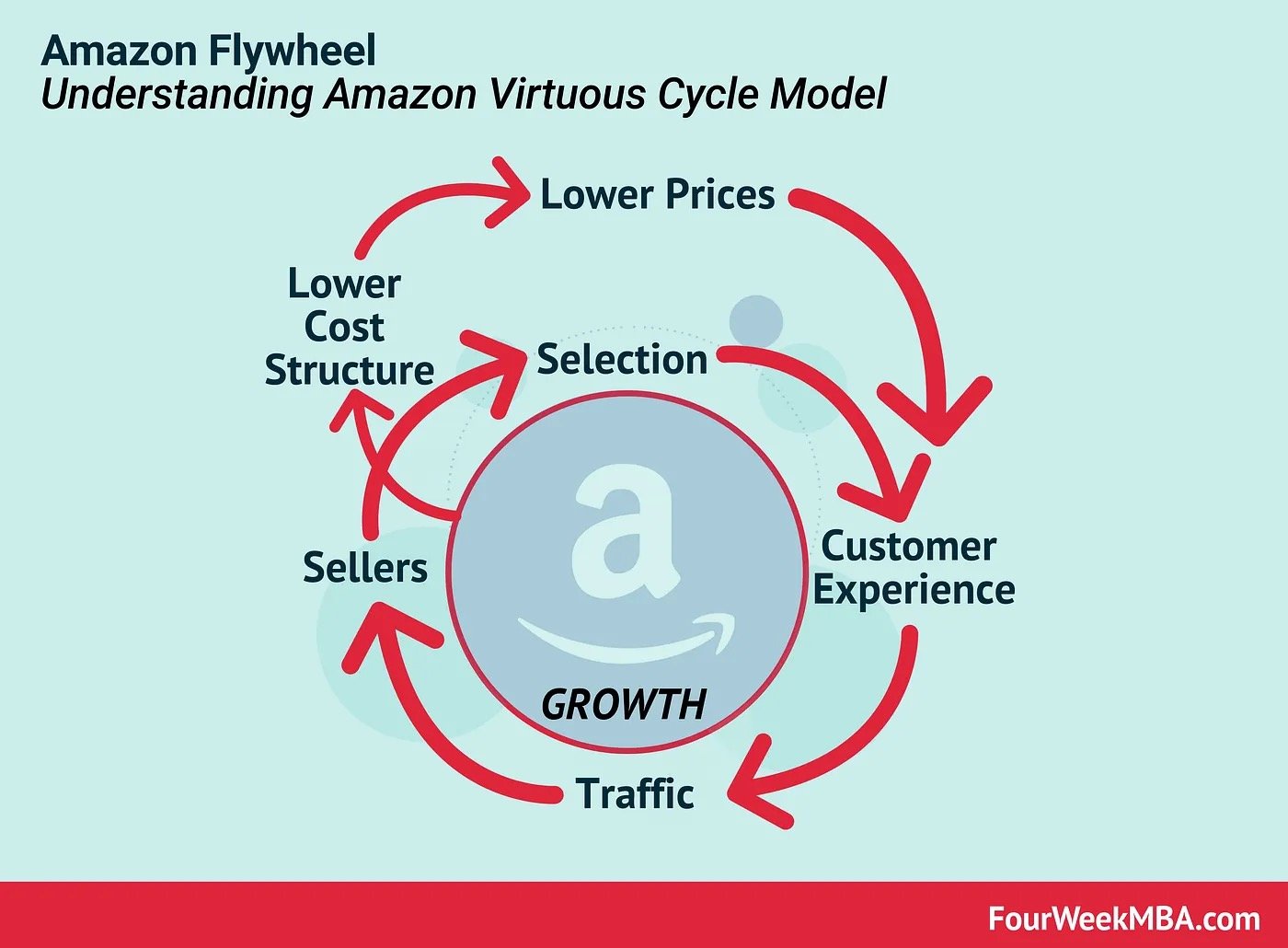

Amazon lives by the motto that frugality breeds resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention. This allowed them to pass the savings to the customer and is tied with its Virtuous Cycle Model. The Virtuous Cyle dictates how reducing costs allows the company to lower its prices, which in turn improves the customer experience. This leads to more traffic and sales, which allows them to both increase their selection and allows them to negotiate lower prices with suppliers. These savings can be then ploughed back into lowering the prices of goods, and so the virtuous cycle continues.

Amazon’s Virtuous Cycle Model

Customer obsession

Amazon is not just customer-centric, it is customer obsessed. Its mission is to figure out what the customer wants, and what’s important to them. Meetings within the organization often have an empty chair to represent the customer’s interests, and whenever a new product or service is proposed, one of the key questions asked are, “What will disappoint the customer most?”

Amazon wanted to take the inconvenience out of online shopping, with the most efficient delivery, and provide the largest offering of products (even if it was rare or highly seasonal). Amazon’s online website has the largest selection in the world — an estimated 350 million products — and is available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The only competitor that comes close to this is Alibaba, with a selection of approximately 330 million products.

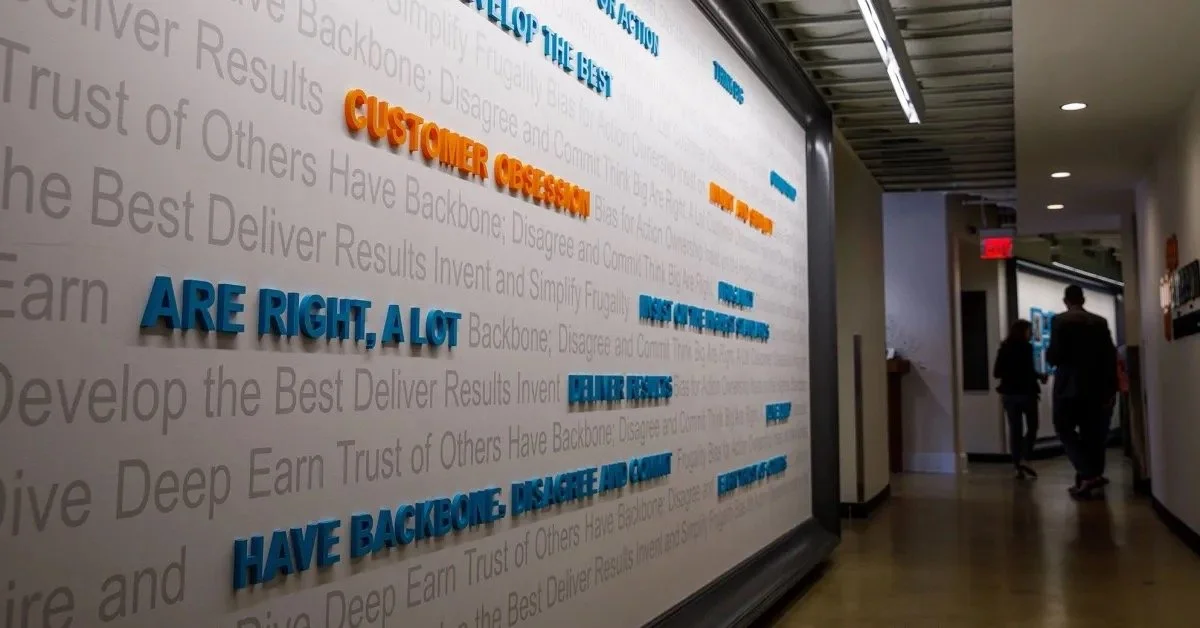

Amazon’s Leadership Principles

Bezos was also insistent on making sure the customer had access to the best prices, even if it meant they would not buy from Amazon, and rather the third-party sellers that advertised their goods on Amazon‘s marketplace. He said,

“If somebody else can sell it cheaper than us we should let them and figure out how they are able to do it.”

The willingness to sacrifice profits in return for customer trust did not always sit well with shareholders and board members, but the short term losses were long term gains. More and more third-party sellers flocked to Amazon’s marketplace, which increased the selection of products available to the client, and increased customer loyalty. Today, third-party sellers account for more sales on Amazon than Amazon’s first-party retail business, and commision from third-party sales represents 19% of their revenue stream.

Amazon also aimed to provide a personalized shopping experience by using collaborative filtering, a technique used by recommender systems. By leveraging the thousands and thousands of data points — clicks, views, purchases — each user generates on their website, Amazon can predict what you are going to buy next, sometimes even before you make the conscious decision to buy that item. They are so confident in their ability to quantify and predict consumer behaviour that they stock up the products in fulfilment centres near you.

Criticism

On their path to success, Amazon made some poor decisions that have damaged its brand. In fact, an entire Wikipedia page is dedicated to criticisms of Amazon. Its ethics and policies have raised eyebrows in some of the highest offices. Recently, Jeff Bezos testified in a virtual antitrust hearing to answer questions about anti-competitive tactics, that lead to a loss of genuine competition and result in public harm, used by Amazon and other Big Tech companies.

Amazon has found many morally-questionable, but legal, ways to minimize its tax burden. For example, even though it made $11.2 billion in profits in 2018, it paid exactly 0% in income tax for that same year. It also received a $129 million tax rebate from the federal government. This is due to a highly complex scheme of carrying forward losses from previous years, tax credits for research and development projects, and stock-based employee compensation. They’ve been accused of actually “building their company around tax avoidance.”

The ugly side of customer obsession and frugality is Amazon’s willingness to treat their blue-collar workers as cannon-fodder in the war for customers’ hearts and wallets. Although workers are generally paid above the national minimum wage, they are subject to harsh and extremely physically-demanding work to ensure that packages are delivered accurately and on time. The fulfilment centres are plagued with workplace injuries. Workers in the fulfilment centres get only two short breaks during eight-hour shift and have to ask for permission to use the bathroom. They often walk up to 14 miles a day (or 22.5km for metric system people) and risk being terminated if they call in sick. Amazon also has a history of shutting down efforts to unionize workers at their fulfilment centres, firing outspoken critics and even firing pregnant workers.

In conclusion

Amazon started as a small online retailer selling a wide range of books, and has grown into a seemingly unstoppable retail giant that still demonstrates double digit growth every year. It is one of the largest employers in the world, with 800,000 permanent employees, and during the holiday season, an additional 200,000 temporary employees. The word ‘Amazon’ has become synonymous with online shopping, in the same way ‘Google’ has become synonymous with online search. The jury is still out on whether Amazon is the villainous exploiter of cheap labour and poorly-written laws, or an efficient empire that expertly traverses the legal tight rope and provide much-needed low-wage jobs to unskilled workers worldwide. Regardless, their rise to Big Tech status, especially following their near-demise during the DotCom Bust, is worth studying.