The DotCom Bubble

June 21, 2020

The iconic San Francisco motel-themed billboards of Yahoo. Sourced from VentureBeat.

I was only about 5 years old when the DotCom Bubble took effect, and while the DotCom Bubble was recent enough to live in most people’s memories and not in the dusty history books, in the technology age 20 years is a millennium. Just look at that billboard, it is practically archaic!

The DotCom Bubble highlighted the pitfalls of greed, over-promising, and ignorance. It also proves an interesting case study for the intricate relationship between innovation, and economic growth.

A DotCom company was called as such because many of them simply consisted of a website. They were online platforms that would facilitate everything from banking to streaming content to buying pet supplies. This was the dawn of the Information Age — an economy built on information technology. The Internet would become as revolutionary as railroads and electricity, bringing people closer together and providing the means of powering new services and markets.

So what preceded the DotCom Bubble?

A number of factors:

The World Wide Web was created in 1989 by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, who wanted to create a globally-connected platform where information can be shared with anyone, anywhere. This sparked the era of globalisation.

Home computers became mainstream — between 1984 and 2000, the percentage of households in the United States with a PC went from 8.2% to 51%.

In 1995, Microsoft Windows 95, which included the first version of the Internet Explorer (another living fossil), went on sale.

A picture begins to form of something that does not grow at a linear pace. Today the Internet is ubiquitous, and we cannot imagine our lives without it.

Jack F. Welch, chairman of General Electric, was quoted in 1999 as saying that the Internet “was the single most important event in the U.S. economy since the Industrial Revolution.”

Back then, the Internet was a very new thing, and people were struggling to grasp its potential. There was anxiety around the commoditization and regulation of the Internet, and there was the fear of the Y2K bug — that computers would misread 2000 as 1900, and that this would cause critical computer systems to collapse. But the Internet was about to revolutionalize we shop, socialize, learn, travel, and more.

Party like its 1999

Although very real and opening up a plethora of new business opportunities, the Internet — combined with free-market economics, low interest rates, and heavy speculation — resulted in a Wild Wild West era for DotComs. It created an over-enthusiastic investor pool that seemingly overnight stopped caring about things like business plans and debt piles. It was also the Internet that enabled buying stocks directly online, which added plenty of less experienced, less sophisticated investors (willing to buy stocks that were overvalued) to the investor pool.

The number of venture capitalist firms also grew by 90% between 1995 and 2000. More money than ever before was made available for startup capital investments. During the same period, 439 DotCom companies went public, raising $34 billion in capital.

Rob Glaser, who founded Progressive Networks in 1994, said, “In 1995 and 1996, if you said you were doing an Internet toaster, I’m sure you could find a venture capitalist to fund it.”

Every tech startup (affectionately identifiable with the .com at the end of their name) was seemingly a unicorn — the next big thing — and everyone had FOMO on the IPO of said unicorn. Many DotCom companies were bandwagon jumpers, with few original ideas, thin business plans, and plenty of big talk. Some spent up to 90% of their budget on advertising to get their brand “out there”.

To add to their net operating losses, they were overpaying average talent and hosting exuberant parties. They also offered their products/services for free or at a discount with the hope that they will create loyal customers whom they can charge profitable rates in the future. The goal was to “get big fast” — identify a niche market early and gain market share as quickly as possible, to shut out all competitors.

Fall from grace

During the early years of the DotCom bubble, investors were willing to forgive DotCom companies for posting losses while they were busy developing their IP and expanding their market share. But after a few loss-making years, investors started to get nervous. Many had become overnight paper millionaires from the skyrocketing IPOs, but as we all should know — share price does not equal fair value nor company performance. Surely the goose will eventually run out golden eggs to lay?

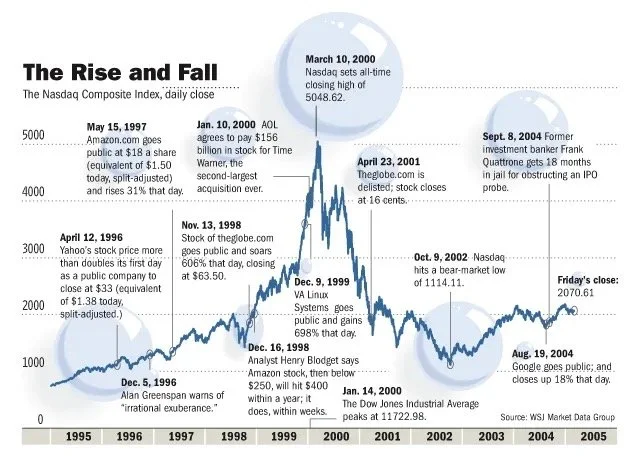

Stock market bubbles, during their ascension, tend to be very sensitive to market shocks. The DotCom Bubble was no different — on March 13, news that Japan had once again entered a recession triggered a global sell-off that disproportionately affected the overvalued technology stocks. This, combined with aggressively-raised interest rates, the events of 9/11, several accounting scandals including that of Enron and WorldCom, sparked a two-year decline in the Nasdaq Composite — comprised overwhelmingly of technology stocks. Many DotCom companies struggled to secure further venture capital, whilst burning through their cash pile. IPOs and further stock offerings was out of the question. Since they were nowhere near profitability and received no cash influxes, they eventually went into liquidation. An estimated 52% of DotCom companies went bust by 2004.

The DotCom bust was a combination of increased scrutiny of DotCom companies’ financials, investor fatigue, and the belief that the Internet was a fad. Of course, the Internet was not a fad, and would soon bring forth a new Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The aftermath

If bubbles popping were extinction-level events, then companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon were the crocodiles of the tech ecosystem. The Big Pop allowed them to become apex predators in their respective fields, for several reasons. Real estate became much cheaper, hardware became easier to obtain, the market was flushed with recently-unemployed, talented software engineers, and the extinction of their competitors allowed them to rapidly gain market share. Today, they are some of the most valuable, and most recognizable brands in the world. Their respective portfolios overlap somewhat and often they compete for market share, as well as talent. In later years, companies like Facebook and Netflix would join their ranks. Within their respective workplaces, each of these tech giants demands extremely high performance from their employees and have a habit of acquiring any potential competition. Collectively, they are called FAANG, and as of January 2020, they have a combined market capitalization of over $4.1 trillion.

Although nearly untouchable today, back then these companies were not immune to the fallout. In the face of diminishing confidence, Amazon’s share price fell from $107 to just $7. Google waited out the DotCom bubble and only launched its IPO in 2004. At the height of the DotCom Bubble, Apple’s share price reached a height of almost $5, only to fall below $1 in 2003.

For Apple, the decade following the DotCom Bubble was most prosperous as it led the innovation of consumer electronics. Apple launched the iPod in 2001 and introduced the iTunes Store in 2003, where users could purchase individual tracks for just $0.99. The iTunes Store hit five billion downloads by June 19, 2008. Apple also released Mac OS X, the primary operating system of Apple’s Mac computers, in 2001. The first iPhone, the integration of an Internet-enabled smartphone and the iPod, was introduced in 2007. And in 2010, they introduced the iPad.

Steve Jobs introducing the first iPhone in 2007.

The innovation that followed the malaise of the early 2000s were led by these apex companies. They invested heavily in new startups and even built the infrastructure (cloud computing) that allowed smaller companies to iterate much faster for much less upfront infrastructure investment.

The DotCom bubble fostered an era of entrepreneurship that has not been seen in the US since before the Great Depression. It provided a petri dish to test out the validity and marketability of a wide range of Internet services. Many of the services were way ahead of their time — like online food delivery and online clothing stores. Unfortunately for these services, the consumer base, technology, and infrastructure simply were not ready.

Today, investors look at tech IPOs with increased scrutiny — the consensus is that one simply does not take a tech company public before it reaches profitability. WeWork, Uber, Lyft — all these companies went public before having showing profitability. They were whipped in the public square — figuratively, of course — with their share prices falling on the day of their respective IPOs.

Closing remarks

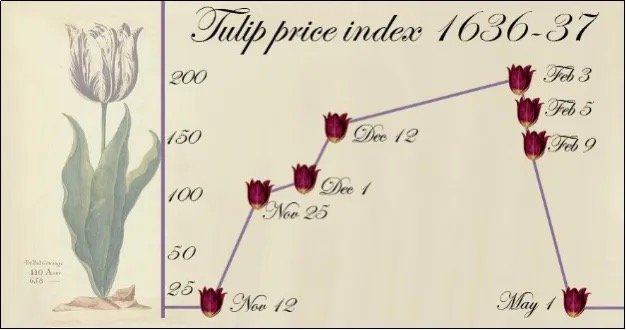

In hindsight, everyone has 20–20 vision. But during a bubble, everyone seems to have these unrealistic, almost fanatical views of what the future would look like. The first recorded speculative bubble dates back to 1636–1637, named the Tulip Mania. At the height of the mania, the bulbs sold for approximately 10,000 guilders — equal to the value of a mansion on the Amsterdam Grand Canal. Investors believed that there would always be a buyer willing to purchase the bulb at a higher price than their entry point. The perceived value of the tulip bulbs became disjointed from their intrinsic value, which was destined for a correction.

Tulip Mania of 1637

While researching the DotCom Bubble, I noted many similarities with today’s manner of market speculation and that of the DotCom Bubble. Trading apps that allow investors to buy fractional shares with zero commission has introduced plenty of young, inexperienced investors to the market, and this has coincided with some of the strangest events in stock market memory. Is history repeating itself? Perhaps the frequency of bubbles coincides with the memory span of investors.

If you enjoy this blog post, please consider supporting my writing by buying me a coffee.